British Celtic-Hilt Heavy Cavalry Undress Sword - Some Thoughts...

Posted: 24/06/20 (14:27pm)As most of you know by now, I have a gorgeous Celtic-Hilt heavy cavalry undress sword and here it is.

The Celtic-Hilt sword was named by Richard Dellar in 1995 and so called because of the circle and swirl patterns on the guard, reminiscent of ancient Celtic symbols and adornments.

This heavy cavalry officer’s fighting (undress) sword first appeared on the battle fields of the Peninsular around 1812, four years after Britain’s entry into the conflict.

So was their appearance on the battlefields of Portugal and Spain a mere fashion statement, or was it due to dissatisfaction with the regulation pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry officer’s ladder-hilt sword?

The Celtic-Hilted sabre was developed by John Prosser, probably in close consultation with one or more Dragoon officers, as a replacement for the regulation pattern Ladder-Hilt Heavy Cavalry sword. The officers, having first-hand experience of the regulation pattern’s inadequacies may well have been the driving force behind the new blade design.

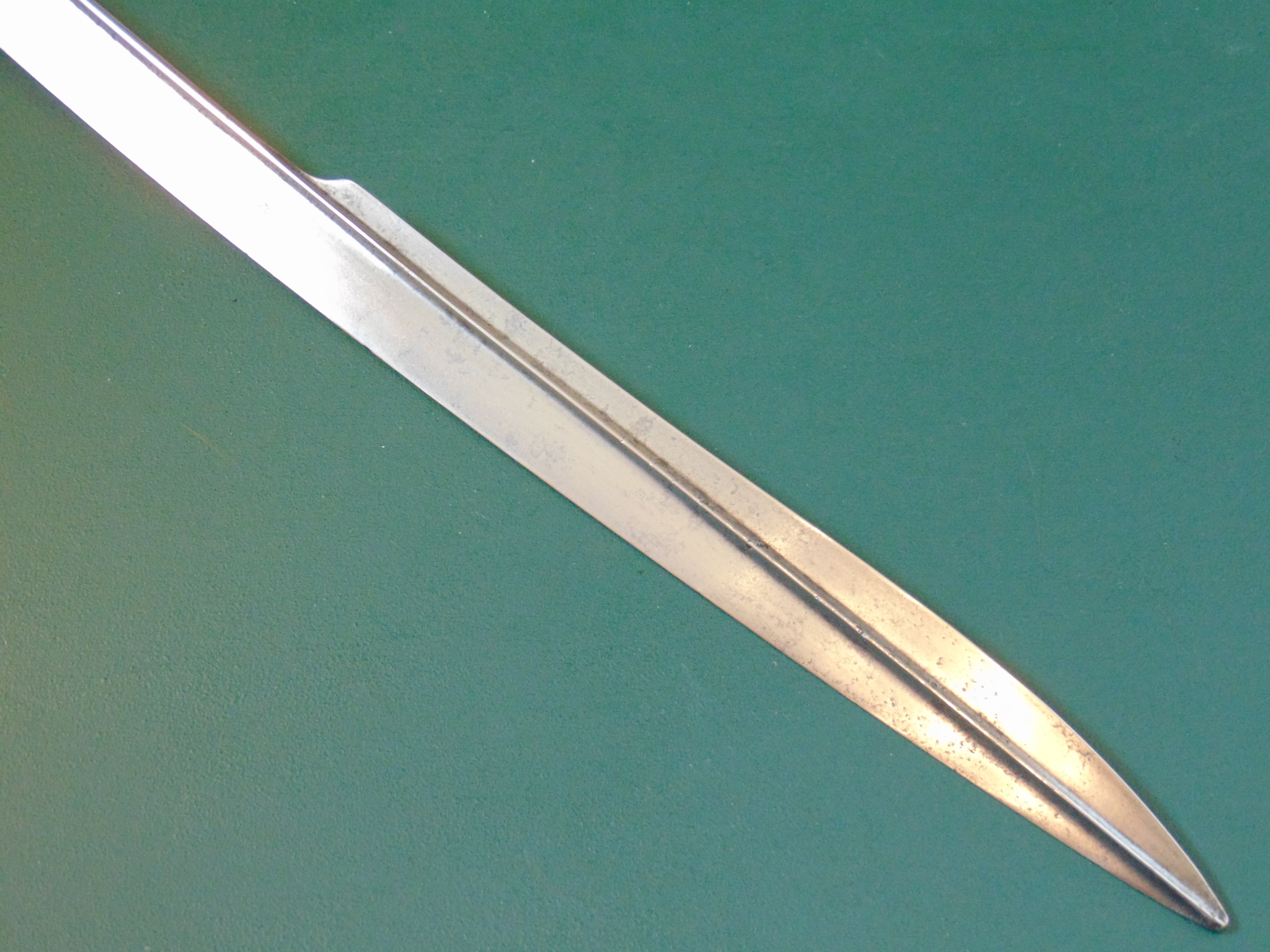

The hatchet-pointed 1796 Heavy Cavalry sword had proved itself ineffective against French breastplates and officers in the Peninsular must have felt at a disadvantage. They would also have been looking to provide themselves with any possible future advantage. Prosser, for his part used his knowledge of Indo-Persian and Ottoman sabres – blades known to have the capability and reinforced point for piercing armour, to develop his patent quill point to pierce the breast plates of French Heavy Cavalry, the Cuirassiers. The impact of the charge would have driven the reinforced point of the new blade into the enemies cuirass, the quill-point with its recurved edges would then have operated like a can opener, the large recurved yelman lengthening and widening the cut to facilitate entry and as importantly, the withdrawal of the blade. The double-edged quill point may also have provided an advantage over single-edged blades in a post charge melee.

The point of my sword is slightly rounded from impact - whether or not this was caused by a French cuirass we will never know. But I believe it to be likely.

It is also worth noting that the sword’s fearsome appearance would have had a mental impact on both the wielder and the intended target. Coming hard on the heels of French complaints about the brutality of the 1796 Light Cavalry sabre and the cuts it inflicted, a new cavalry sword with a vicious-looking point must have caused quite a stir amongst French cavalrymen.

Despite being credited for the design and development of the Celtic-Hilt sword, Prosser was not the only maker to have supplied them, although only individual examples are known from other makers and all post 1812. Just as officers would have had a preferred tailor, so too would some have had a preferred sword maker and this might explain the single examples by other makers.

Known examples that have regimental attribution are all named to the Dragoons; the 4th Dragoons in particular. One example exists in the Edinburgh Castle museum, Scotland, marked to the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (although the officer who owned it served with the 4th Dragoons in the Peninsular). Another example held in the Edinburgh Castle museum is marked to the 3rd Dragoons. It is known that the 3rd and 4th Dragoons shipped to Portugal and billeted together throughout the Peninsular Campaign.

So why were so few of these sabres made? The short answer is that we will probably never know for sure, but there are several acceptable explanations and the likelihood is that it will have been a combination of several reasons. Initially, news about the new sword would have been slow to circulate to other branches of the cavalry, perhaps explaining why the sword seems to have been used almost exclusively by the 4th Dragoons. Snobbery and one-upmanship amongst the officers may have also played a part. The 4th dragoons may have felt that it was “their sword.”

In 1821 a new pattern was accepted as regulation for the heavy cavalry and perhaps the lee-way allowed to officers in choosing a sword to take to war was reduced in peacetime, forcing them to adhere to regulations. Maybe the quill point was not as effective as initially hoped? Maybe the sword was just too expensive to make for the enlisted cavalryman? Whatever the reasons, by 1821 the Celtic-Hilted cavalry sword had passed into obscurity and is now extremely rare.