Posted: 24/12/22 (11:49am)Wow! Another year has flown by and no blog from me. Apologies. Must try harder (that sounds familiar)

It has been an interesting year for us all. A lot has happened, near and far, good and bad.

Thank you for your support and custom throughout 2022.

However you spend this time of year Sue and I hope it is enjoyable and trouble free.

Wishing you all a happy and healthy 2023.

Best wishes,

Richard & Sue

Posted: 24/12/21 (9:44am)Happy Christmas Everyone!

However you celebrate this time of year, or whether you celebrate at all, Sue and I want to wish you well.

It has been my pleasure doing business with you all and I thank you sincerely for your custom and support. I look forward to dealing with you all in 2022.

Have a safe, healthy and happy Christmas and New Year.

Posted: 18/08/21 (10:21am)The model 1816 Cuirassier (Heavy Cavalry) trooper’s sword at first glance is very similar to the previous Mle AN XI Napoleonic period Cuirassier’s sword.

On closer inspection they are actually quite different. The Mle 1816 is the culmination of the evolution of the French heavy cavalry sword that began in 1802.

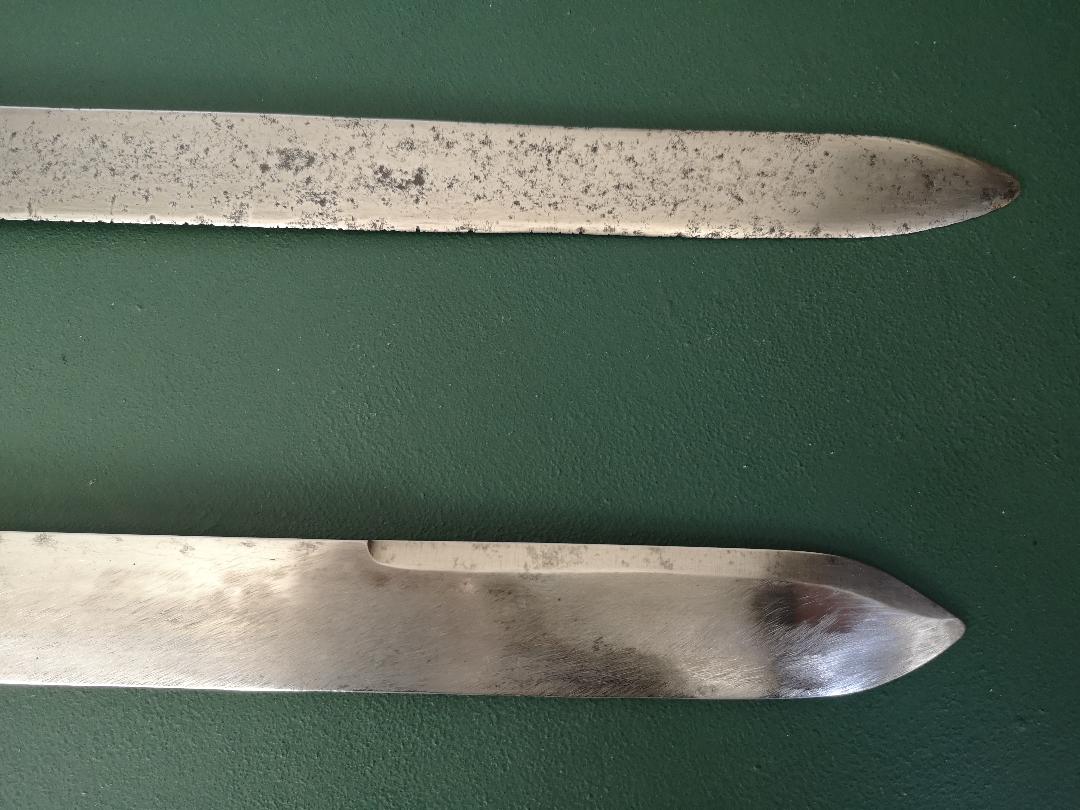

The main differences are in the grip, slight changes to the four-bar guard, pommel cap and the longer blade with rounded spine. That said, many Model 1816 swords utilised the earlier AN XI blade which was approximately 45mm shorter and has a flat spine.

As a picture is said to be worth a thousand words, here are some photos of the Mle 1816 and AN XI swords showing the differences and similarities.

French Mle 1816 on left. French mle AN XI on right.

French Mle AN XI Cuirassiers' sword.

French Mle 1816 Cuirassiers' sword

French Mle 1816 with a 998mm spear point blade

AN XI with a 965mm hatchet point blade

From 1814 onwards AN XI had their hatchet points re-ground to a spear point resulting in a 955mm blade.

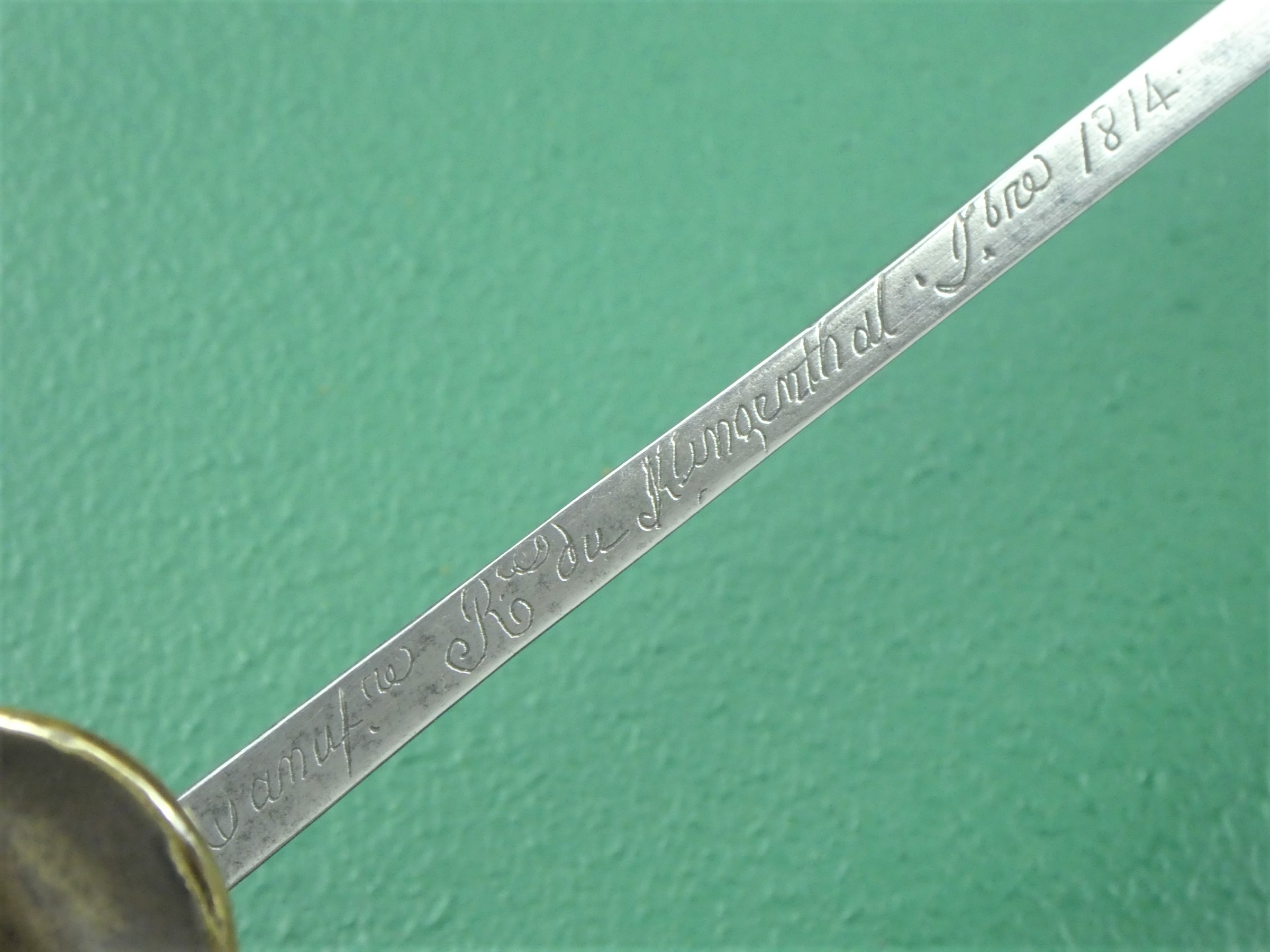

Mle 1816 rounded spine. This example made at Klingenthal in February 1820.

AN XI flat spine. This example made at Klingenthal in 1814

So at first glance, two very similar swords. On inspection however, really rather different.

Posted: 20/10/20 (14:19pm)I hope that this blog finds you all well. Finding things to blog about has not been easy of late. All our lives and daily routines have been discombobulated by Covid-19.

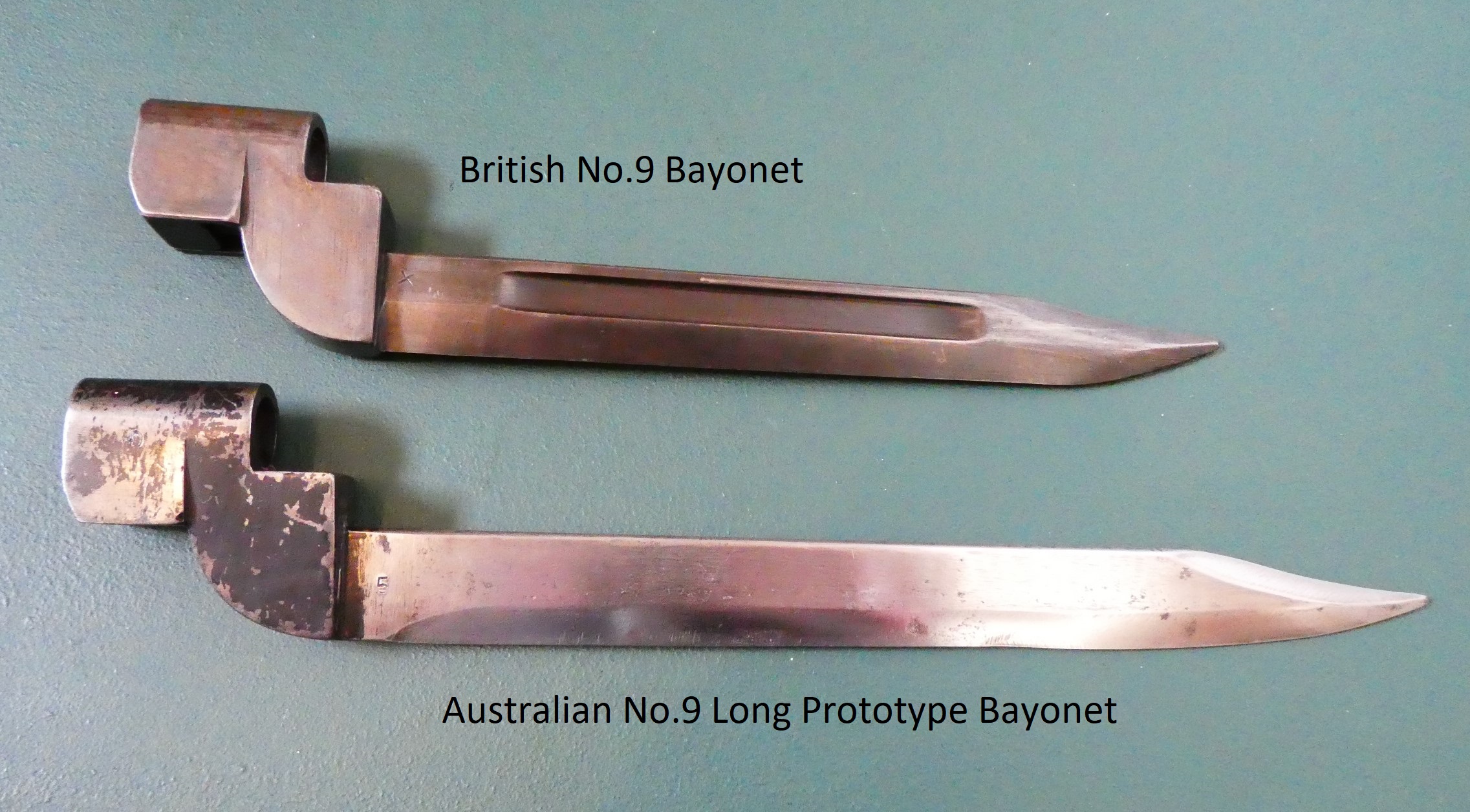

But now, I truly have something to get excited about! I have come into possession of an extremely rare bayonet and thought it would be worth sharing it and my observations. In the absence of an official designation, I am calling this bayonet the "Australian No.9 Long Prototype Bayonet."

It is thought that these prototype bayonets were made in the 1950’s. Little more is known about them as so few were made and no official documentation has been released.

Ian Skennerton & Robert Richardson in their book, “British and Commonwealth Bayonets,” describe this bayonet in the “miscellaneous” section, suggesting that its origins are “unknown.” It is interesting to note their interpretation of the socket block marking as being DAD, when in fact it is D^D, the Australian Defence Department mark.

The Australian Department of Defence stamps and Mk1, Owen type scabbard indicate that this was clearly an Australian project.

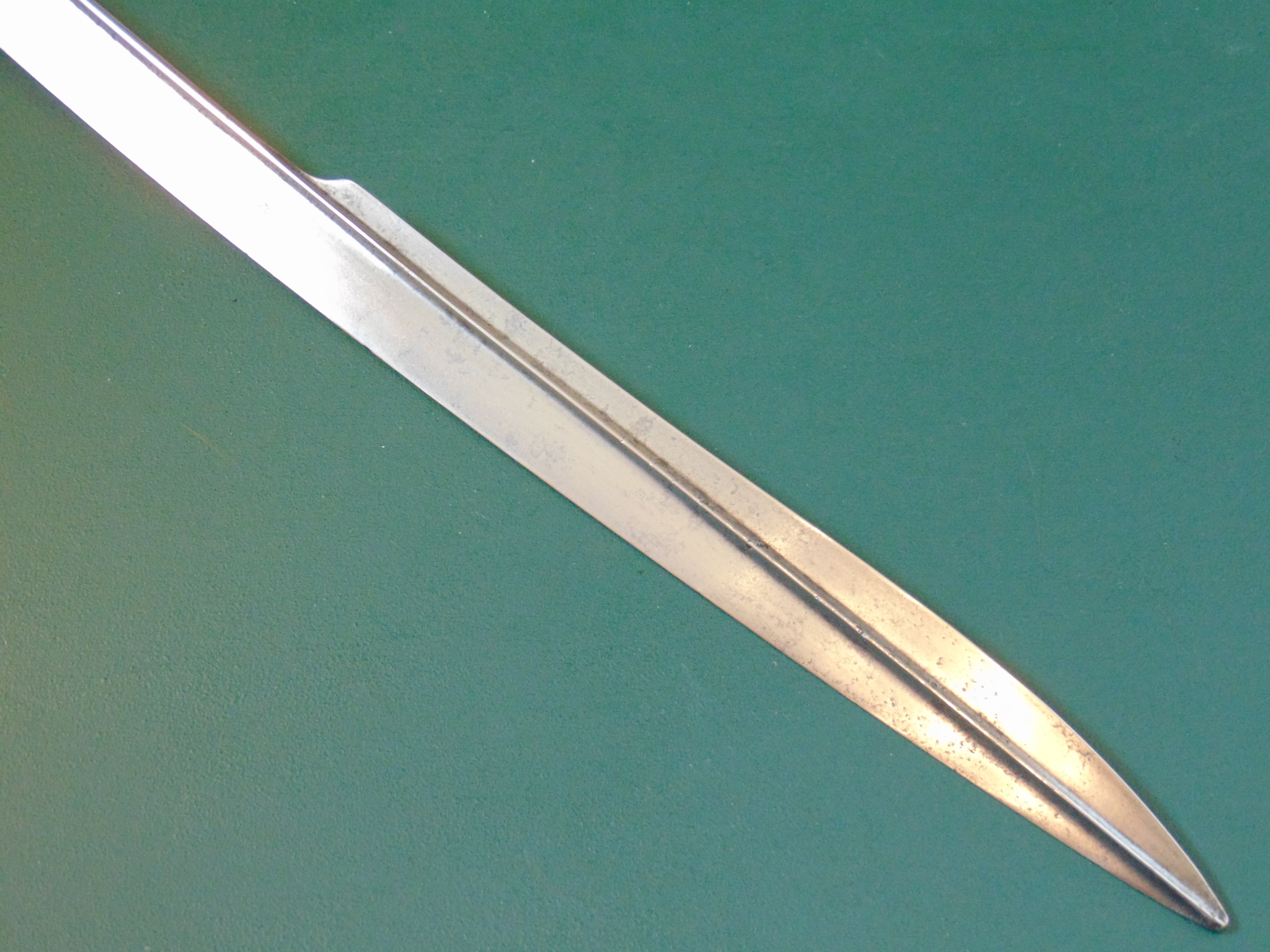

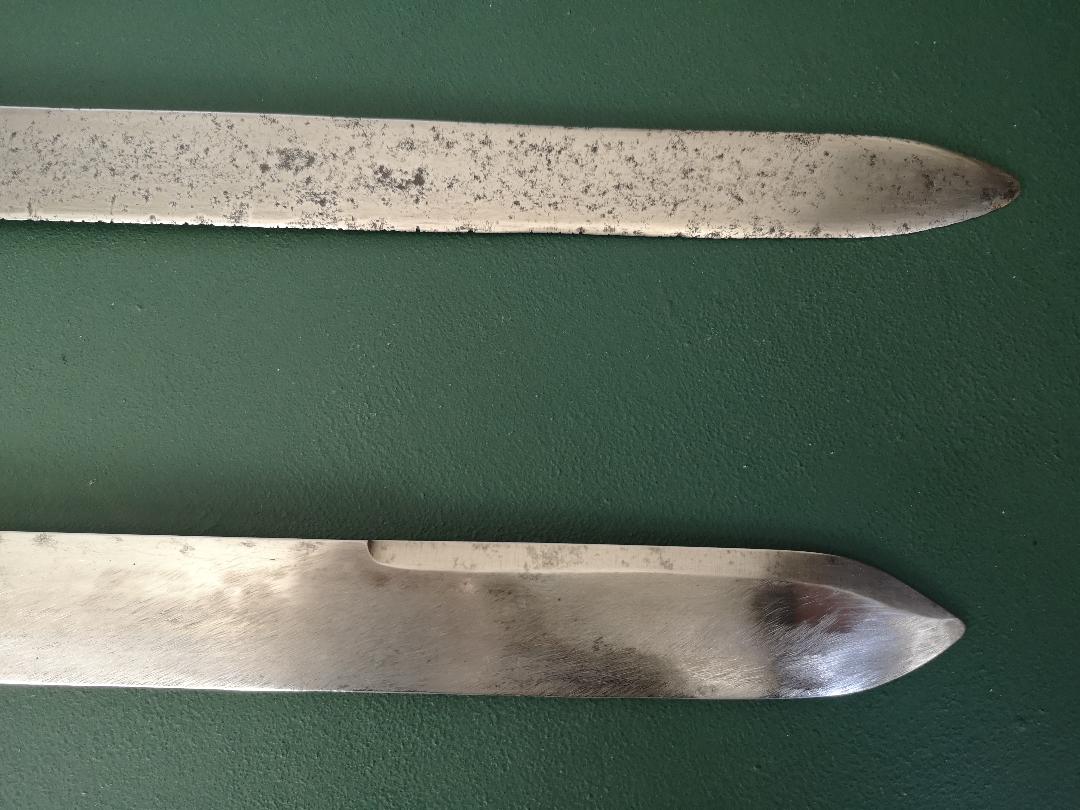

The 250mm Bowie style blade has a slightly rounded spine terminating in a sharpened clip-point. The un-fullered blade has an “apple seed” grind to the edge. The forte of the blade is stamped with the numeral 5, which probably indicates the 5th Military District (Western Australia).

The blackened steel socket is the same as that of the British No.9 bayonet. The muzzle ring diameter is 15.2mm. The right side of the socket block bears the Australian Defence Department stamp of an arrow within a capital D. The left side of the socket block is deeply struck with another numeral 5 and another Australian Defence Department stamp, the previously mentioned two capital D’s with an arrow between.

The top of the locking catch plunger bears a British War Department arrow and an Enfield factory stamp. This is the same style of stamp, a capital D incorporating an over stamped E & F that was used on the Enfield produced No.9 bayonets. The front of the block is also stamped with an Enfield factory mark and the inspection number 165. This indicates that the socket block was a British No.9 block made in the UK.

Interestingly, British No.9 bayonets produced by the Enfield factory have the pattern designation, No.9 Mk I and a much larger factory mark as well as the production date stamped on the left side of the block. The absence of these stamps on this block could indicate that although the block itself was produced by the Enfield factory in the UK, its production was specifically for the prototype bayonet at the request of the Australian Defence Department. It would make sense for this to have been the case as the necessary tools and infrastructure to produce the block were already in place in the UK.

The bayonet is sheathed in a shortened No.1 Mk II scabbard, also known as the Owen scabbard. The locket and chape bear Lithgow factory marks.

As mentioned earlier, I believe that the presence of the Australian Defence Department stamps and the use of a shortened Mk 1 Lithgow made scabbard indicate that this is an Australian prototype bayonet loosely based on the British No.9. Why it never went into production is unknown but it is likely that the arrival in the late 1950’s of the new 7.62 NATO cartridge and the Belgian made FN rifles had something to do with it.

Whatever the case, this is an incredibly rare and exciting prototype bayonet from a pivotal period in the history of rifle and bayonet design.

Posted: 24/06/20 (14:27pm)As most of you know by now, I have a gorgeous Celtic-Hilt heavy cavalry undress sword and here it is.

The Celtic-Hilt sword was named by Richard Dellar in 1995 and so called because of the circle and swirl patterns on the guard, reminiscent of ancient Celtic symbols and adornments.

This heavy cavalry officer’s fighting (undress) sword first appeared on the battle fields of the Peninsular around 1812, four years after Britain’s entry into the conflict.

So was their appearance on the battlefields of Portugal and Spain a mere fashion statement, or was it due to dissatisfaction with the regulation pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry officer’s ladder-hilt sword?

The Celtic-Hilted sabre was developed by John Prosser, probably in close consultation with one or more Dragoon officers, as a replacement for the regulation pattern Ladder-Hilt Heavy Cavalry sword. The officers, having first-hand experience of the regulation pattern’s inadequacies may well have been the driving force behind the new blade design.

The hatchet-pointed 1796 Heavy Cavalry sword had proved itself ineffective against French breastplates and officers in the Peninsular must have felt at a disadvantage. They would also have been looking to provide themselves with any possible future advantage. Prosser, for his part used his knowledge of Indo-Persian and Ottoman sabres – blades known to have the capability and reinforced point for piercing armour, to develop his patent quill point to pierce the breast plates of French Heavy Cavalry, the Cuirassiers. The impact of the charge would have driven the reinforced point of the new blade into the enemies cuirass, the quill-point with its recurved edges would then have operated like a can opener, the large recurved yelman lengthening and widening the cut to facilitate entry and as importantly, the withdrawal of the blade. The double-edged quill point may also have provided an advantage over single-edged blades in a post charge melee.

The point of my sword is slightly rounded from impact - whether or not this was caused by a French cuirass we will never know. But I believe it to be likely.

It is also worth noting that the sword’s fearsome appearance would have had a mental impact on both the wielder and the intended target. Coming hard on the heels of French complaints about the brutality of the 1796 Light Cavalry sabre and the cuts it inflicted, a new cavalry sword with a vicious-looking point must have caused quite a stir amongst French cavalrymen.

Despite being credited for the design and development of the Celtic-Hilt sword, Prosser was not the only maker to have supplied them, although only individual examples are known from other makers and all post 1812. Just as officers would have had a preferred tailor, so too would some have had a preferred sword maker and this might explain the single examples by other makers.

Known examples that have regimental attribution are all named to the Dragoons; the 4th Dragoons in particular. One example exists in the Edinburgh Castle museum, Scotland, marked to the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (although the officer who owned it served with the 4th Dragoons in the Peninsular). Another example held in the Edinburgh Castle museum is marked to the 3rd Dragoons. It is known that the 3rd and 4th Dragoons shipped to Portugal and billeted together throughout the Peninsular Campaign.

So why were so few of these sabres made? The short answer is that we will probably never know for sure, but there are several acceptable explanations and the likelihood is that it will have been a combination of several reasons. Initially, news about the new sword would have been slow to circulate to other branches of the cavalry, perhaps explaining why the sword seems to have been used almost exclusively by the 4th Dragoons. Snobbery and one-upmanship amongst the officers may have also played a part. The 4th dragoons may have felt that it was “their sword.”

In 1821 a new pattern was accepted as regulation for the heavy cavalry and perhaps the lee-way allowed to officers in choosing a sword to take to war was reduced in peacetime, forcing them to adhere to regulations. Maybe the quill point was not as effective as initially hoped? Maybe the sword was just too expensive to make for the enlisted cavalryman? Whatever the reasons, by 1821 the Celtic-Hilted cavalry sword had passed into obscurity and is now extremely rare.

Posted: 12/05/20 (14:02pm)Yesterday I added a short sword to the website that I initially identified as being an early Napoleonic Wars period British artilleryman’s hanger. You can view it in the “Newly Added” section of the website. By early I meant that it was made a few years before the Osborn made hanger that I also have on the website and which dates to between 1800 and 1807. At first glance the two swords are very similar.

Osborn Artilleryman's Hanger 1800-1807

AH1 Unmarked Artillery Hanger

AH2

After time in the hand, and having studied them closely, I now think that the newly added sword is actually a refinement of the original and not a predecessor. I must admit that the scabbard threw me. But let’s set the scabbard aside for now and come back to that later.

An examination and comparison of the swords themselves suggests that the hanger made by Osborn is the earlier of the two. You can view the Osborn hanger by following the link below.

https://www.bygoneblades.com/buy-british-napoleonic-wars-artillery-gunners-short-swordThe Osborn hanger is dateable to between 1800 and 1807. The second hanger (let’s call it AH2 and the Osborn AH1) was probably made after gun crews gave battlefield feedback.

AH1 below. AH2 above.

Let’s look at some stats:

Sword Dimensions AH1 AH2 Total length 754mm 785mm

Weight 1020g 775g

Blade length 635mm 665mm

Point of balance 165mm 135mm

Spine thickness

at shoulder 10mm 8mm

Spine thickness

at midpoint 6mm 3mm

Blade width

at shoulder 37mm 37mm

Blade width at

convergence to point 34mm 29mm

Upper false edge 145mm N/A

As you can see, the Osborn made hanger, AH1 is a much heavier sword with a shorter, thicker blade. It is a very blade-heavy and unwieldy weapon. With a sharpened edge it would have been a devastating cleaver but slow to recover to guard, meaning a missed cut would throw the wielder off balance and leave them open to a counter attack by their opponent. It would also have been poor in the thrust. Hanger AH2 by comparison is longer, better balanced and significantly lighter while still having the width and weight to afford a devastating cut. The sharpened spear point is also thin enough to deliver a reasonable thrust – albeit probably not through a thick woollen tunic.

AH1 below. AH2 above AH2 AH1

AH2 is a far better fighting sword, it is lighter and faster in the hand, its shorter point of balance and better distal taper enabling a faster recovery from cut to guard and from cut to thrust. These improvements are almost certainly as a result of feedback from the field.

The fighting style of enlisted gun crews was probably more akin to frantic slashing and hacking than schooled swordsmanship, and the reduced weight and improved balance of AH2 would definitely have afforded them a better chance of surviving a close quarter fight.

In January 1809, after retreating from Napoleon’s Army of Spain, General Sir John Moore’s 35,000 men fought heroically against Marshal Soult at the Portuguese port of Corunna. Despite winning, they suffered heavy losses (including Sir John Moore) and were shipped back to England.

Reinforced and re-equipped, the British army returned to Portugal in May 1809 under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley (later The Duke of Wellington). I believe that improved Artillery hangers like AH2 would have been issued to gun crews of the returning army.

Artillery hanger AH2 is without maker or military ownership marks, but this is not unusual. The need for equipping the troops for the return to the Peninsular superceeded inspection and acceptance marking. It is also possible that the absence of a Crown ordnance stamp means that the hanger was purchased by one of the volunteer battalions raised at the time and was therefore not the property of the Crown.

So now let’s address the scabbards.

AH2 Scabbard without brass throat and with an elongated frog stud.

Initially, the construction of the scabbard belonging to AH2 led me to believe that it was an earlier model than AH1. The lack of a metal throat and the elongated frog stud in particular appear to harp back to an earlier age. So could it be the wrong scabbard for the sword? It is certainly possible. But I don’t think so. The fit to blade is excellent so I am pretty sure that the scabbard was made for this hanger. I think the answer lies in the period in which these weapons were made and used.

In Georgian England, a regiments’ commanding officer was responsible for arming and equipping the men under his command. He was given an allowance from the Crown and free reign to choose from whom he purchased. Numerous manufacturers were involved in the fabrication and supply of weapons and each would have had slight variations on patterns and options on quality and price. It was not uncommon for commanding officers to try to reduce costs in order to pocket the difference. Leather scabbards without brass throats with smaller and less ornate chapes would have been by far the cheaper option.

So in conclusion, I now believe that artillery hanger AH2 is of later production than hanger AH1 albeit by only a few years, and that the apparently earlier period scabbard of AH2 is in fact simply a cheaper, while perfectly serviceable option.

AH1 and AH2 are both very rare and were in service during the Peninsular and Waterloo. An ideal opportunity to grab yourselves a piece of history!